UNBOUND10!

July 2nd – August 7th, 2021

ANNUAL JURIED + INVITATIONAL EXHIBITION

INDEX

[JUMP TO ARTIST]

• KYOHEI ABE • FRANCESCO AMOROSINO • RYAN BAKERINK • SOPHIE BARBASCH • MICHAEL BOROWSKI • ANNETTE LEMAY BURKE • ADRIENNE CATANESE • BARBARA CIUREJ + LINDSAY LOCHMAN • ELIZABETH M. CLAFFEY • JASMINE CLARKE • PAMELA LANDAU CONNOLLY • ISABELLA CONVERTINO • ROBIN CROOKALL • NANCY DALY + KIM LLERENA • SHANNON DAVIS • CAROL ERB • BRANDON FORREST FREDERICK • JOHN FREYER / ANNE MASSONI / BETSY SCHNEIDER / BECKY SENF • RYAN FRIGILLANA • DANA FRITZ • TERI FULLERTON • DANIEL GEORGE • IRIS GRIMM • PAUL GUILMOTH • SOOMIN HAM • ALICE HARGRAVE • JESSICA HAYS • KEVIN HOTH • KEI ITO • JOE JOHNSON • GIOVANNA LANNA • CHRISTIAN K. LEE • JIATONG LU • HOLLY LYNTON • SARAH MALAKOFF • NOELLE MASON • ELIZABETH MCGRADY • CAROLINE MINCHEW • ROBYN MOORE • COLLEEN MULLINS • SCOTT MURPHY • RACHEL PHILLIPS • MIORA RAJAONARY • MEGAN RATLIFF • RENEE ROMERO • KATHERINE DEMETRIOU SIDELSKY • PAUL STEPHENSON • DANA STIRLING • ELIZABETH STONE • JERRY TAKIGAWA • PAUL THULIN-JIMENEZ • VAUNE TRACHTMAN • AARON TURNER • JULIE WOLFE • TRICIA WRIGHT •

KYOHEI ABE

Imagined Futures: Untitled #2, 2021. Archival Pigment Print, 28 x 28 inches. Edition of 10. $3500, Framed

Most of my images are built upon a formula, a structure of both space and content. I was originally trained as an architect and designer, so I tend to build compositions that are clean, well ordered, and simple in content and composition.

In my creative process, I always look for juxtapositions and interrelationships that create new perceptions and new meanings. I always discover a structure, or some form of order within. I then look for a more complex system existing within the simpler structure. In the end, the results of this exchange of elemental play between images, space and myself are attractive. Photography is a medium that fosters the belief that we have the ability to preserve reality, when in fact the reality we thought to be recorded actually exists in the conceptual space between viewer and imagery.

All my images are the result of combining physical construction and digital technology. They are constructed with multiple images that are individually captured, then cropped and stitched, which results in superior resolution – a perfect illusion. I feel that the result of presenting in hyper-real resolution is to draw viewers deep into my works, suspending their disbelief and dazzling at the intersection of illusion and reality.

FRANCESCO AMOROSINO

Quod Oculus Non Videt, 2020. Liquid Silver Gelatin Emulsion on Marble, 4.50 x 4.50 x 1.20 inches. Unique. $950

Damnatio Memoriae, 2020. Liquid Silver Gelatin Emulsion on Marble, 6.70 x 4.30 x 0.60 inches. Unique. $1000

These two pieces are part of a larger series, In Medias Res

The life of each one of us starts “in medias res” (in the middle of the events in latin): we arrive in a world that has already a history. There are more things we don’t know than we can learn, we are born in pieces, we all are archeologist of ourselves and of the word that surrounds us. To live without being crushed by the weight of what has come before is for sure an heroic act. Nevertheless we have to pick the fragments and build our own destiny. Technique: Liquid silver gelatin emulsion on marble and stone.

RYAN BAKERINK

The Loop - May 31st, 2020. Archival Pigment Print, 26 x 30 inches, Framed. Edition of 25. $1200, Framed.

In a year that brought layers of complexities in an already complex city, this body of work expanded beyond what was meant to be journey of self-exploration, into a time capsule of Chicago in a year 2020.

Just over 20 years ago at the age of 20, I moved to Chicago from a small farming community in South West Iowa. The year 2020 is symbolic for my time spent in this city. Throughout the course of a single year, I set out to understand my place in the Chicago, why I was drawn to the city, and how it has shaped who I have become.

During this journey, I adapted to the unique circumstances and challenges presented throughout the year while maintaining the integrity of the original scope of the project. I tackled this self-discovery while navigating through social unrest, political unease, an economic collapse, and through a pandemic. While wearing a protective mask to explore the city, I uncovered hidden treasures among the emptiness, beauty in humanity, and empowerment through injustice.

This work evolved far beyond its original intention in the most symbolic possible way. Throughout a single year I was emotionally, socially, mentally, and physically challenged while trying to simultaneously document a city experiencing similar challenges. By presenting the work in sequential order, I ask the viewer to go on this journey with me as it unfolds.

SOPHIE BARBASCH

Adam's Blonde Wig, 2019. Archival Inkjet Print, 20 x 24 inches, Unframed. Edition of 5 + 2AP. $2200, Unframed.

Growing up in my family was difficult, and so I have always tried to get distance from it. But it’s as if my family members, and our relationships, hold some secret, or key. I find myself continually returning in order to resolve yet another question. Like a magnet, I alternately seek and repel these people who have defined the emotional cornerstones of my life.

A family is a shifting conglomeration of narratives and feelings, just as each individual is constantly evolving and adapting. In the midst of a long estrangement from my father, I bonded with my younger cousin Adam, who I could not help but feel was like my double. Looking at him brought me back into the fault lines of my childhood; he was an entry point into storylines that I needed to rewrite through my own lens.

Much has changed since I started this project in 2013, but the same theme drives me: the mutability and inscrutability of each one of us. The more I press down, looking for definitions and truths, the more illusory everything becomes. At first, I was obsessed with conveying my own conclusions; today, I question those conclusions—I question the certainty of my own story. This experience has a liquid quality; relationships come and go like waves.

As Adam experiments with his gender presentation, making forays into dresses and make-up, I find yet another way to connect with him. Growing up in a family of men, I was often the only girl, which influenced power dynamics in both mundane and problematic ways. In the photos, I play with visualizing and subverting these dynamics.

I need photography not only for what it shows us, but also for what it doesn’t show us—for what it fails to do, for what it keeps hidden. This is what I seek to capture within the frame: not the answers so much as the fact that there are none. I find strange comfort in this; it confirms my experience and pushes me to confront each subjective moment for what it is—boundless, indeterminate, quietly electric.

MICHAEL BOROWSKI

Through the Swift, Black Night 02, 2019. Archival Pigment Print, 16 x 24 inches, Framed. Edition of 10. $600, Framed

With the current expansion of cameras integrated into smart devices there is a need to critically examine machine vision. My series Through the Swift, Black Night depicts the landscapes of Appalachia through 360-degree LiDAR scanning. Part of an ongoing exploration of rural science fictions, these black and white point cloud images speculate on the impact of autonomous vehicles on the region. The series questions the analogy of the camera to the human eye, expanding notions of what a photograph can be and how it records the surrounding world.

ANNETTE LEMAY BURKE

Airport Approach, Palm Springs, CA, from the series Fauxliage, 2019. Archival Pigment Print, 18 x 24 inches, Framed. Edition of 15 + 3AP. $1000, Framed.

As a Silicon Valley native and longtime observer of the evolution of the western landscape, I’m interested how we interact with the natural world, the landscapes constructed by the artifacts of technology, and how our environment changes over time.

In my project Fauxliage, I explore the odd juxtaposition of disguised cell phone towers in the landscape and how technology and our built environments are encroaching on nature. Are we willing to have an uncanny valley of manufactured landscapes in exchange for five bars of service? The tower camouflages also cloak the cellular equipment’s covert ability of collecting all the personal data transmitted from our cell phones.

ADRIENNE CATANESE

Peaches, from the series, In Absentia. Archival Pigment Print on Aluminum Panel, 20 x 20 inches. Edition of 10. $1250.

In Absentia is a photographic series about trauma and survival. In 1998, at age 14, I was raped by a 21 year old who groomed me and my friends in early internet chat rooms. Building props and constructing meticulous still life, I use objects as surrogates to form a narrative of my rape which is both personal and political. In this work, surreal images evoke the cognitive sensations of traumatic memory, and the lawless nowhere-ness of the early internet. In Absentia operates within a sort of dream logic: nothing is as it should be, and I cannot seem to awake.

In this post- #metoo moment, we are still reckoning with rape culture. Victims are disbelieved, denigrated, subjected to erasure: famous rapists are household names, but can we name any of their accusers? Trial in absentia is considered a violation of defendants’ rights, yet victims’ stories and collective histories remain absent from our cultural narratives. Indeed, archival documents from my own legal case defend the character of my rapist, even as my personhood remains conspicuously absent from the files. In Absentia’s compartmentalized box-like images unpack my individual experience while raising the larger question: how many unseen others carry similar boxes of trauma, shame, and invisibility?

BARBARA CIUREJ + LINDSAY LOCHMAN

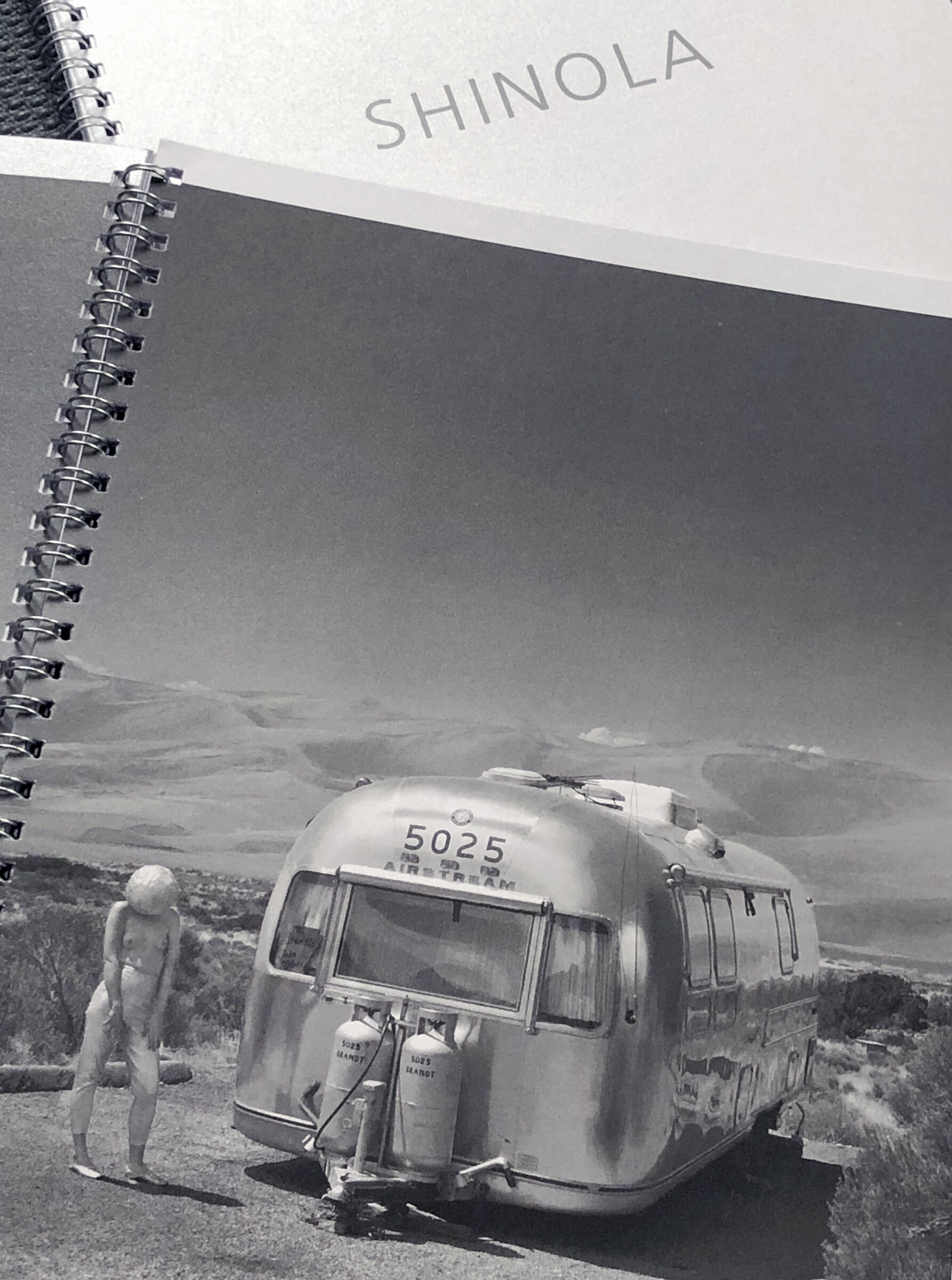

Shinola, Digital Prints on Silver Cardstock, Spiral Bound, 10 x 8 inches, 24 pages. Edition of 35. $35

This much we know…

Long, long ago, phantasmagoric voyagers traveled through time, thrumming with the energy of the Big Bang.

We recognize kinship and yearn to connect with these unencumbered creatures of light.

Sightings were reported — split second glimpses, like lightning in the desert monsoon.

We call out to them in silvery voices.

We park our vehicles, scan the skies, and await electrifying deliverance.

ELIZABETH M CLAFFEY

Interior 29, 2020. Archival Pigment Print, 24 x 32 inches, Framed.

$1500, Framed.

Darkness and Nothing More explores the nighttime landscape of family life, as well as identity formation and performance. At night, I check on my children over and over, at first because they require it but later because it soothes my own anxieties. After they fall asleep, I get to watch them at a distance – with my body intact, untouched, un-smothered – and see them, still. They seem small again. Their slow breaths fill me with warmth while slight movements challenge my nervous system for fear that I’ve been too brazen, lingered too long in this moment where everyone is here and safe. The familial labor and love that happens at night is incredibly intimate, and moving through darkness is a metaphor for parenthood itself. Nighttime is when the heart rate slows, body temperature drops, and our mammalian instincts for physical closeness heighten. The sensory longing for touch, the compression of another body, is what often wakes my children in the night and has us all moving through the dark to find one another.

On our way, I find small clues of their inner lives: rocks carefully placed throughout the hallway, ribbons mark the spaces between their fantasies. I photograph these still lives like they are clues to a larger mystery, evidence, or communication of a story nobody will tell. At times, our bodies become the surprise revealed in the night because during these years, we are body on body on body, performing gestures that bring our bodies closer to each other and eventually, closer to ourselves, given the power for those gestures and movements to shape our identities. As this ongoing work develops, I turn my gaze toward my partner because intimacy is a significant part of our bond. These works are a way of reclaiming the experience of desire so often denied women in their postpartum lives despite how much that sensuality can reinforce the rich experience of family life. I also photograph my mother as her aging and our reciprocal care is intertwined with the mothering of my children.

As our daughters get older, they have become more nervous about nighttime. They too worry that something might go wrong, a mystery that is not their own might be lingering outside our door or in their closet. I tuck them in at night, promising to check on them, and tell them to rest assured. It’s Darkness and Nothing More.

JASMINE CLARKE

Olivia, Looking, 2018. Archival Pigment Print, 25 x 20 inches, Framed. Edition of 4. $500, Framed.

When I look in the mirror, I want to believe that what I am seeing is an extension of myself even though I know that it isn’t. I am seeing a reflection (an illusion) of me and my world. I can never quite trust a mirror.

A picture creates a similar false sense of reality. The nature of photography tells us that what we are seeing is true, but it’s not. It is a selective truth, or even a fiction.

One night in Jamaica, as my father and I drove through the mountains, he described a recurring dream: he is in his hometown, Saint Mary's, at a certain winding road that’s shaped like an N, trying to catch the bus. He misses it and has to run up the mountain through the bush and slide down the other side to catch it. This is his only dream set in Jamaica. He told me as we approached the N. I listened while chewing on my sugar cane. It’s strange hearing about a dreamscape while physically going through it—like déjà vu.

I feel this sense of familiarity driving through my father’s dream. But what’s more overwhelming is the sensation of jamais vu: foreignness in what should be known. The moon you see, the air you breathe, and the flowers you smell are all suddenly unfamiliar. You’ve moved, traveled—maybe even transcended—although you don’t know to where. You look in the mirror and see yourself, but can’t be sure that it’s the same reflection you saw yesterday.

This is why I photograph: to capture a trace of the unexplainable. My pictures are where dreams meet the physical world and earthly things take on higher meaning. I search for the uncanny. I uncover what is hidden. An obscured face, a wet flower, a dark shadow.

ISABELLA CONVERTINO

Brothers, 2018. Archival Pigment Print, 13.6 x 13.3 inches, Framed. Edition of 10. $600, Framed.

"to shoot the sun" is a reflection on trauma and experience with masculine energies, as well as an investigation of white landscapes. In this body of work, I forge suburban geographies to create a terrarium. Here, I am able to direct and deconstruct performances of gender, and to consider the relationship between intimacy and power. Bleaching light and homogeneous landscapes trap subjects in an immobility and overexposure; bodies are contained, muted, and observed. They are fastened to a mode of waiting— and a process of decomposition— by way of a caustic light. I work to contain and study male power, observing its growth and erosion, and sourcing its construction and relegation.

ROBIN CROOKALL

Real Spaces: Lamp Shade, 2020. Gelatin Silver Print, 19.5 x 26.4 inches, Framed. Edition of 5. $2400, Framed.

Real Spaces: Cactus and Lamp, 2019. Gelatin Silver Print, 26.4 x 19.5 inches, Framed. Edition of 5. $2400 Framed.

My work is a blend of sculpture and photography. The subjects of my images are

assembled sets of exteriors and interiors. With a collage of elements, my work creates scenes consisting of part fact and part aspect.I construct architectural models which I photograph, and print. For these models, I primarily use cardboard, tape, and hot glue; unsophisticated materials that retain a certain cogency and drabness when captured in a photo. Focusing on subjects like the corner of a room or the facade of a house, the images showcase environments that are at once familiar and safe, underwhelming and routine, creating something broadly accessible. What the audience sets out to experience in the photograph changes in perspective from visualizing the subject as an actual photographed place as opposed to seeing what is really its scale-model counterpart. The experience results in the viewer questioning the preexisting notions of reality, memory, and place. Complex abstractions result in the intersection and overlap of those perceptions. The photograph is the ideal pedestal for these concepts, for its singular capacity for both depiction and deception. If you can’t trust your own eyes, then you can’t trust your own definition of place. And where are you supposed to exist at the plane of the image if all that grounds you, is slowly dissolving away? The pursuit of the uncanny drives to create a particular kind of illusion. Not the big flashy kind, where an elephant disappears right before your eyes, but the subtlety of the card-counter, the sleight of hand, and unnoticeable graceful dance of the pickpocket. I am not a wizard, there is no real magic here. The best tricks are the ones we don’t even see.

NANCY DALY + KIM LLERENA

Crater Lake National Park, OR (family), from the series, American Miniature, 2019. Archival Pigment Print, Walnut Plywood, Plexi. 36 x 8 x 10 inches. $600

Horseshoe Bend, Page, AZ (umbrella), from the series, American Miniature, 2019. Archival Pigment Print, Walnut Plywood, Plexi. 36 x 8 x 12 inches. $600

Archival Pigment Print, Walnut Plywood, Plexi

American Miniature is a recent collaboration between Kim Llerena and Nancy Daly; presented here is part two of a two-part project. On the gallery floor, small snapshots of tourists acquired on three cross-country road trips are mounted at the tops of large, pedestal-like objects, transforming these anonymous travelers’ passing moments into a collection of tangible souvenirs.

Souvenirs are inherently and inextricably linked to place, but their value relies on them becoming divorced from that place and re-contextualized in an entirely new one – usually a shelf with other similar trinkets. The site from which the object was purchased becomes secondary, an abstract backdrop that enhances or rounds out the memory.

Wall Drug Store, Wall, SD (tourist/Mt. Rushmore), from the series, American Miniature, 2019. Archival Pigment Print, Walnut Plywood, Plexi. 47.50 x 8 x 10.60 inches. $800

The tourists in these snapshots punctuate and often obscure the views of the pristine landscapes they are photographing or posing in front of, highlighting how awkwardly we tend to interact with an environment when it’s one we’re unfamiliar with. The large size of these new souvenirs compels viewers to move their bodies as they interact with them – crouching, standing on tip-toes, or tilting their heads as if peering at their phones. The tourists posing in the images appear oblivious to their surroundings, while the gallery viewer navigating around the objects is made acutely aware of theirs.

SHANNON DAVIS

Pollen, 2021. Archival Pigment Print on Canson Platine, 16 x 20 inches. Edition of 5. $1120, Framed.

My photographic work often explores the role of place and identity. Atlanta is known as a city of transplants. Being one myself and living here longer than anywhere else, has made me consider the assimilation that takes place when you are an outsider. You bring your past, your assumptions, and your own interpretations to understand the unfamiliar.

To explore this theme, I use the approach Walker Evans employed in his Found Object series, where he stated, “Objects say more about the social psychology of its occupants than the inclusion of the occupant in the image.” Using personal and Southern Gothic stories, I combine familiar domestic objects in uncommon assemblages to illustrate these narrative experiences.

My intent in this photographic project is to connect the audience of transplants and locals using wit and juxtaposition of the art directed still life’s to convey paradoxical observations and cultural challenges while navigating a new place. The combinations straddle real vs contrived, becoming a metaphor for not only the shared universal feeling of being out of place but invites the viewer to questions what is being represented.

CAROL ERB

Tabletop Cruise, Los Angeles, 2021. Archival Pigment Print, 18 x 23 inches, Framed. Edition of 15. $825, Framed.

As a photographer, I try to illustrate ideas and concepts that cannot be seen through the lens. I construct my images digitally from multiple captures, based on ideas and concepts that are often rooted in western culture, from the Ancient Greeks and the Bible, to modern philosophers, like Jean Paul Sartre. Sometimes my images come from a feeling I have, nothing more.

I was a shy and solitary child, with a mind that wandered. In my quiet corner, I watched, becoming an astute observer of the world around me. My closest friends were covered in fur and purred, or stuffed with button eyes that never blinked. I loved the big wild woods behind our house and all the wonderful secrets it held. Drawing and painting came naturally, and would follow me to adulthood.

My mother would tell you that I’ve never been influenced by anyone, that I am wholly original and unique, but that’s not really true. My older sister bought me a large book of work by Rene Magritte, which became dogeared from my eager fingers. I watched Twilight Zone, and Monty Python’s Flying Circus. And I read books, lots and lots of books.

A few years ago, I traded my pencils and paintbrushes for a digital camera and Photoshop. There is a feeling of euphoria that I feel, creating my images with these new tools, when they come to life on my screen.

FOTOFIKA

John Freyer / Anne Massoni / Betsy Schneider / Becky Senf

FotoFika 2020 All Stars, 2021. Photography Baseball Cards, 3.50 x 2.50 x 0.75 inches. $500

FotoFika 2020 All Stars Trading Card Project (2020Allstars.org) includes images from 380 photography students. We invited all photo students from the Class of 2020 across the globe to submit a single image and a statement about their work. We’ve welcomed the work of all graduating students in photography regardless of degree type. We’ve been sharing the work and promoting the project on Instagram and on our sites (including fotofika.org). There was no cost to the students to participate.

Created as a loose interpretation of Mike Mandel’s iconic Baseball Cards, the FotoFika 2020 All Stars celebrates the photography students in the Class of 2020 and serves as a way to introduce their work to reviewers, critics, curators and institutions that will be a part of their future as practicing artists.

With the help of Becky Senf (Center for Creative Photography), we invited professionals in the field to select and review student images in order to build out our “2020 All Stars”; we provided them with student websites for further engagement to contextualize their selection. Our goal was to have 134 (the number of “players” in Mandel’s original card set) curators, writers, critics, photographers and alumni of the original cards to participate as reviewers for the All Stars. Each reviewer had the option to have their own black and white portrait card produced and over 100 opted to do so.

We will produce a physical set of cards and uncut sheets that will be made available for inclusion in collections around the country. Cards will be made available in packs or uncut sheets for purchase for the participants, reviewers and anyone else who is interested. This is where we need to raise money, in order to fund the printing and to provide each of our 380 students with a deck of cards that includes their image.

BRANDON FORREST FREDERICK

Comfort (and to relax), 2019. Archival Pigment Print in Artist's Frame, 15 x 12 inches, Framed. Edition of 8 + 2AP. $450, Framed.

Photography is central to my practice, because of its approximation to reality and its prevalent use in daily life. I use the camera as a tool to capture performative gestures that contribute to and explore what photography means in the context of an image-saturated landscape—one that is inescapably linked to the absurdities of our modern economic reality.

My newer work is predicated on a personal form of recycling. I repurpose discarded objects, signifiers of things that have been consumed and left behind that I find while walking through the city. These everyday objects find their final resting place constructed in my studio or composed in the world. In both staged and found tableaus, I arrange objects in an intuitive and questionable manner—stacking, balancing, and taping objects in moments of near collapse in staged still lifes and contrasting portraits of discarded containers or advertisements with the reaching hands of a model against a dreamy sky. These compositions are inspired by the process of collage, and artists ranging from the surrealist stylings of Dora Maar to newer interrogators of photography like Thomas Albdorf, Paul Mpagi Sepuya, and Stephanie Syjuco.

In exhibition I coordinate these constructions with other photographs that are blended into this process, engaging things found in the world like signs, plants, and appropriated images through social media—sifting for patterns in our collective behavior and sense of identity to reference, amplify or distort.

I see my work as a process to demonstrate the power of our expectations to form what we believe is valuable and to develop a sense of care that comes with deep observation.

RYAN FRIGILLANA

Starved, 2020. Archival Inkjet on Hahnemühle Photo Rag Baryta 315gsm, 20 x 16 inches. Edition of 5 + 1AP. $1100, Framed.

Human connection is vital to our survival and well-being. In light of the global events of 2020, that need has never been more apparent. The Weight of Slumber is an exploration of a singular yet universal experience of grief as it unfolded during the most unprecedented of times.

From the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing lockdown I found my grief and loneliness immeasurably compounded by the abrupt end of a near-six-year relationship. Quarantined and faced with the sudden loss of intimacy and physical contact, I began forming a connection with, and harboring an attuned sensitivity to, the immediate spaces and objects around my home. From the smallest insects to the chorus of rain marching down my gutters; from the snow blowing in through my window living and dying on my bed, to the found photographs I obsessively collected—everything seemed to whisper with weighted words. Sought in the heart of all things: a prayer, a song, an embrace.

Deep in the vacuum of isolation, I yearned for the familiarity of touch, of love and comfort. During this time, these images served as vehicles of reconciliation and escape—a simultaneous mirror and compass through grief. Meditations on space, proximity, surface, and ephemerality, recreate the mental landscape of loss and longing I have been struggling to navigate.

DANA FRITZ

[Pocket] Field Guide to a Hybrid Landscape, 2020. Archival Pigment Prints on Awagami Kozo Thin White and Murakumo Kozo Select White Paper; Accordion Bound. 4 x 5 x .5 inches, closed; 20 pages + 6 flags. Edition 1 of 4 + 1AP. $500

[Pocket] Field Guide to a Hybrid Landscape, 2020. Archival Pigment Prints on Awagami Kozo Thin White and Murakumo Kozo Select White Paper; Accordion Bound. 4 x 5 x .5 inches, closed; 20 pages + 6 flags. Edition 1 of 4 + 1AP. $500

Field Guide to a Hybrid Landscape makes visible the forces that shaped the Nebraska National Forest at Halsey, once the world’s largest hand-planted forest. Wind, water, planting, thinning, burning, decomposing, and sowing all contribute to its unique environmental history. A conifer forest was overlaid onto a semi-arid grassland just west of the 100th meridian in an ambitious late 19th century idea to create a timber industry, and to change the local climate. At that time, tree-planting was not considered in terms of carbon sequestration, but as a way to mitigate the wind and evaporation of moisture and to bring order to a disorderly landscape.

While the planners seemed not to appreciate the particular grassland ecosystem of the Nebraska Sandhills managed through grazing and fire until dispossession, they did recognize the reliable water from the Dismal and Middle Loup Rivers that bound the site. Later it was discovered that under all those grass-stabilized sand dunes was the massive Ogallala Aquifer that feeds the rivers through springs. This seemingly unlimited source of water below made it possible to plant a forest on the dry land above where the wave pattern on the riverbeds is mirrored in the larger scale sand dunes. In 1902, the first federal nursery was founded to produce trees for the new forest and for plains homesteads. That same year a forest reserve was officially established in the grasslands where 31 square miles of trees would be planted.

Historical fire suppression and misguided plantings, (some never taking hold, and others that have become invasive,) present ongoing management challenges for foresters. While afforestation is no longer in practice at Nebraska National Forest, the on-site Bessey Nursery now grows replacement seedlings for burned and beetle-damaged National Forests in the Rocky Mountain region as well as the Nebraska Conservation Trees Program. This unique experiment of row-crop trees that were protected from the natural cycle of fire for decades, yet never commercially harvested for timber, provides a rich metaphor for our current environmental predicaments. This hybrid landscape has evolved from a turn of the 20th century effort to reclaim with trees what was called “The Great American Desert” to a focus on 21st century conservation, grassland restoration, and reforestation, all of which work to sequester carbon, maintain natural ecosystem balance, and mitigate large-scale climate change.

TERI FULLERTON

on the before side, 2019. Archival Digital Inkjet Print, 21 x 16 inches, Framed. Edition of 10. $1200, Framed.

that has been

The snapshot is identified as photography at its most innocent. Yet the photographic trace of a friend or loved one carries a significant existential weight. What then is the currency of a stranger?

I collect vintage snapshots and formal portraits, the ones left behind that have become a commodity. There is a search for what Roland Barthes refers to as “that has been”. “Death” he says, “is the eidos (essential nature) of the photograph.” They are embedded with issues of mortality, memory and nostalgia.

Among the most interesting of insights provided by these photographs is the universality of our history; you did yesterday what I do today. We find patterns and insights- or at least look for them. It is the search for meaning, from self-definition to the human condition that draws us in.

Along with the collected photographs; objects, words, drawing, present day digital images are combined. They act as memorials and totemic offerings and hint at the illusion of the three-dimensional adding shadow and depth to the long past moment.

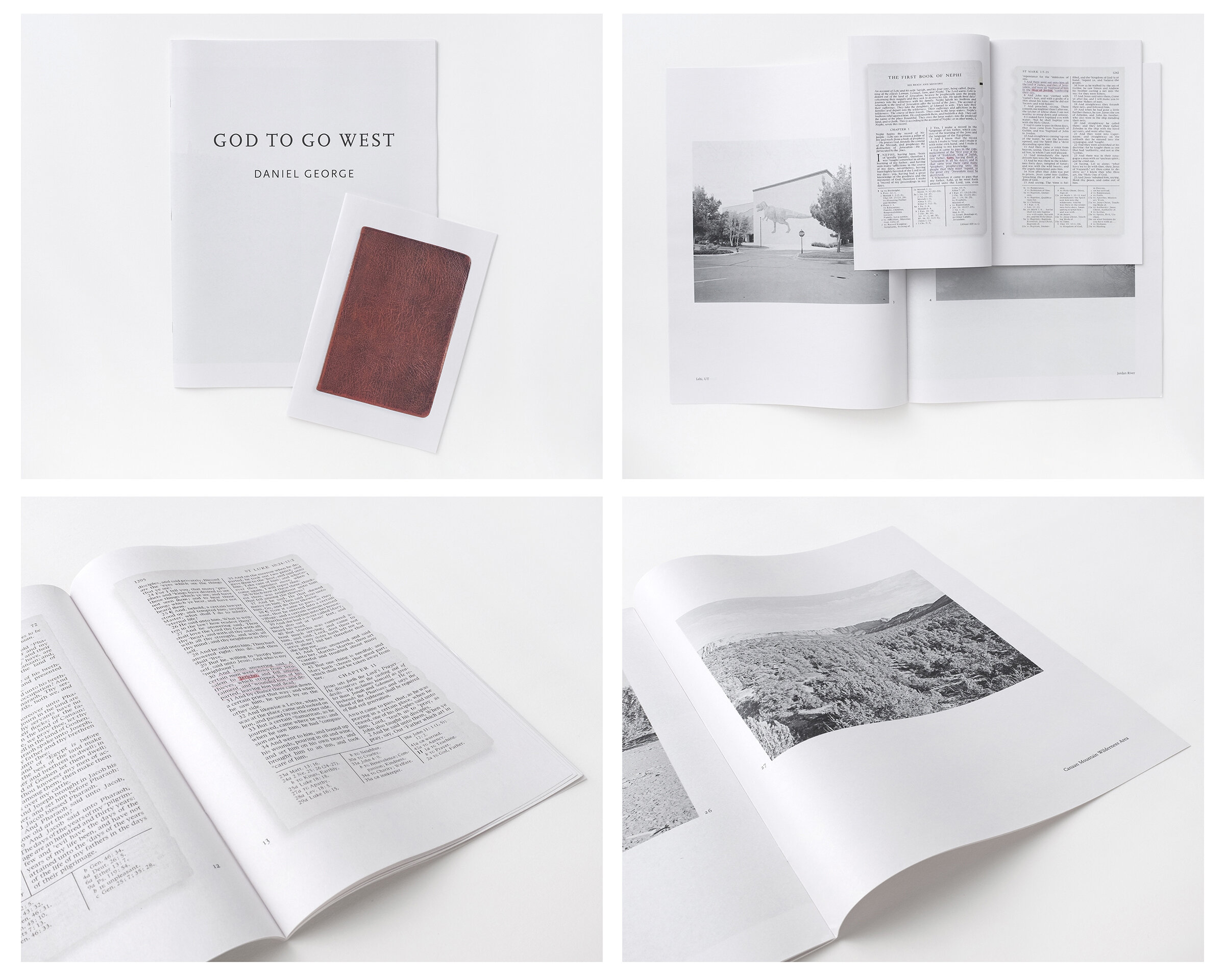

DANIEL GEORGE

Daniel George, God to Go West, 2020. Newsprint, Staple-Bound, 15 x 11.5 inches, 42 pages, 31 plates. Edition of 50. $35

These photographs, from various projects completed over the past several years, represent my interest in the interconnection of place and culture as it relates to communal and personal identity. My photographs often attempt to visualize and understand the idiosyncrasies of human activity in the local cultures within which I reside.

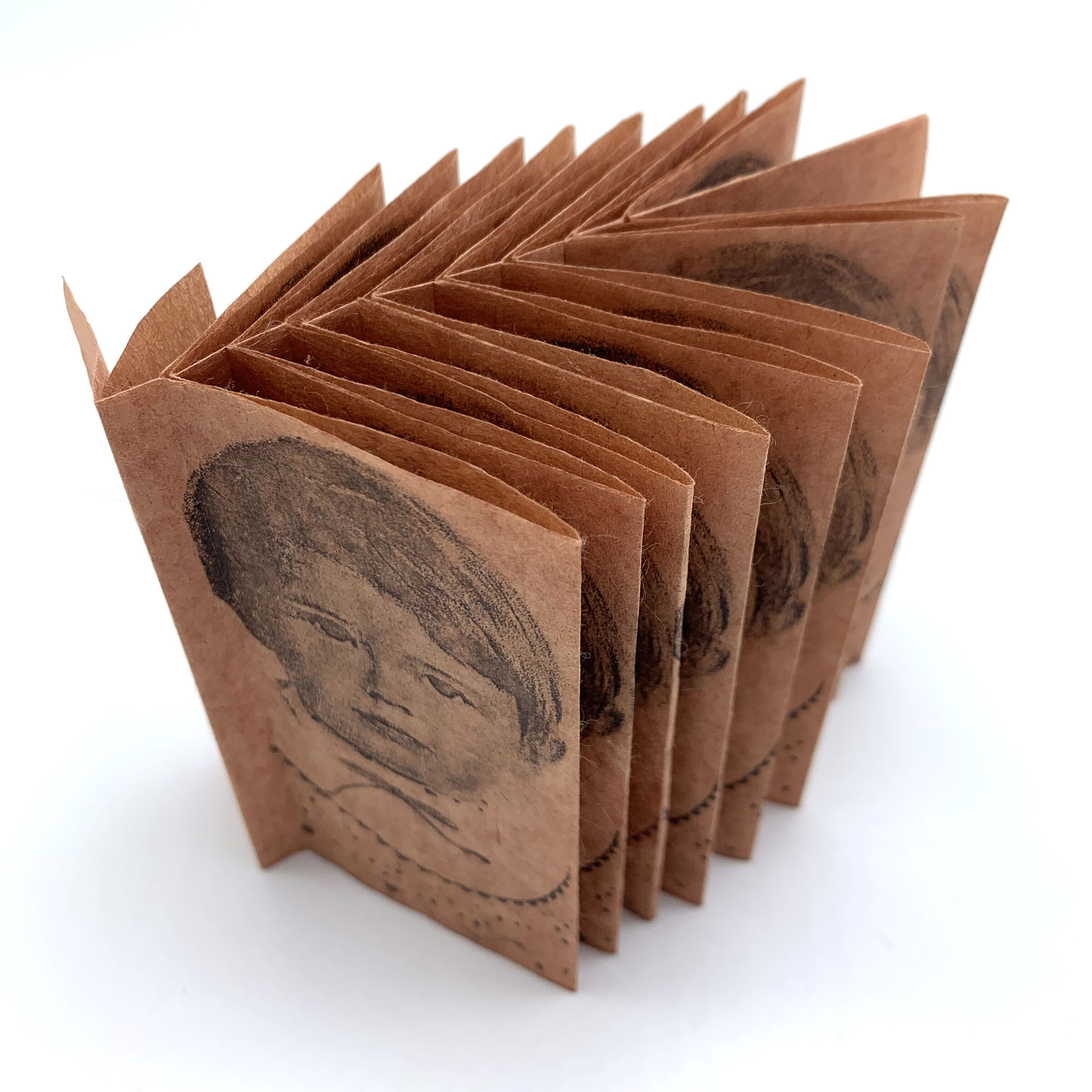

IRIS GRIMM

Far Between Kin, 2019. Handmade Box, Kaji Paper Dyed with Handmade Ink, Fishbone Fold Book, Antique Family Photo, Xerox Transfer, 4.5 x 6.38 x 2 inches. Unique. $600

Far Between Kin, 2019. Handmade Box, Kaji Paper Dyed with Handmade Ink, Fishbone Fold Book, Antique Family Photo, Xerox Transfer, 4.5 x 6.38 x 2 inches. Unique. $600

Far Between Kin, 2019. Handmade Box, Kaji Paper Dyed with Handmade Ink, Fishbone Fold Book, Antique Family Photo, Xerox Transfer, 4.5 x 6.38 x 2 inches. Unique. $600

My current body of work utilizes repetition to draw attention to subtle differences and ignite curiosity. I address themes of change, the passage of time, truth and perception. I’m particularly interested in interpersonal perception and how truth and facts are malleable.

PAUL GUILMOTH

My work is a constant collaboration with my immediate surroundings: my family, neighbors, friends, and the environments surrounding my home. I search for landscapes that are queer and symbols that are fluid. I attempt to mythologize rather than document: to show both a place and its ghosts.

How To Go Fly Fishing Attempt #17, 2020. Archival Pigment Print, 20 x 16 inches, Mounted. Edition of 5 + 1AP. $1200, Mounted

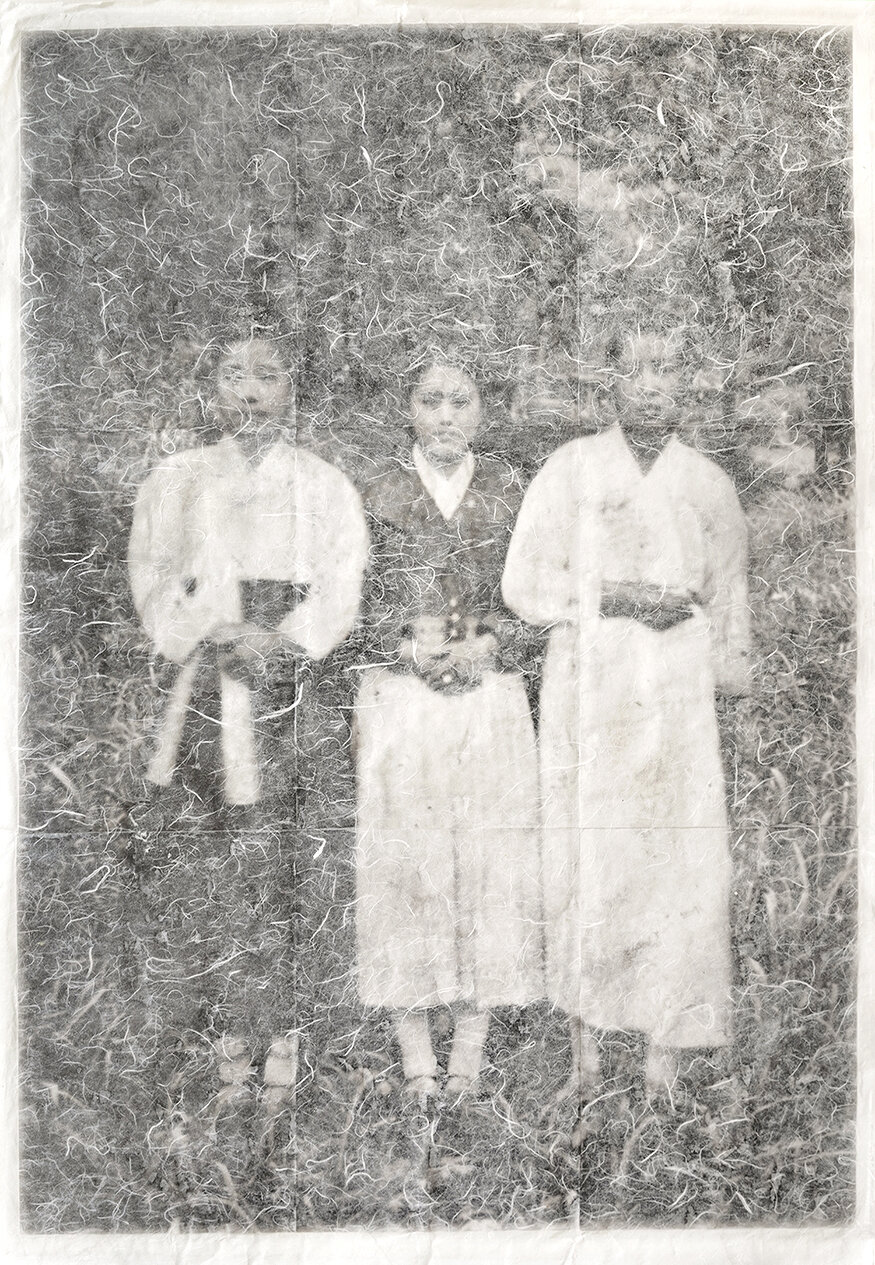

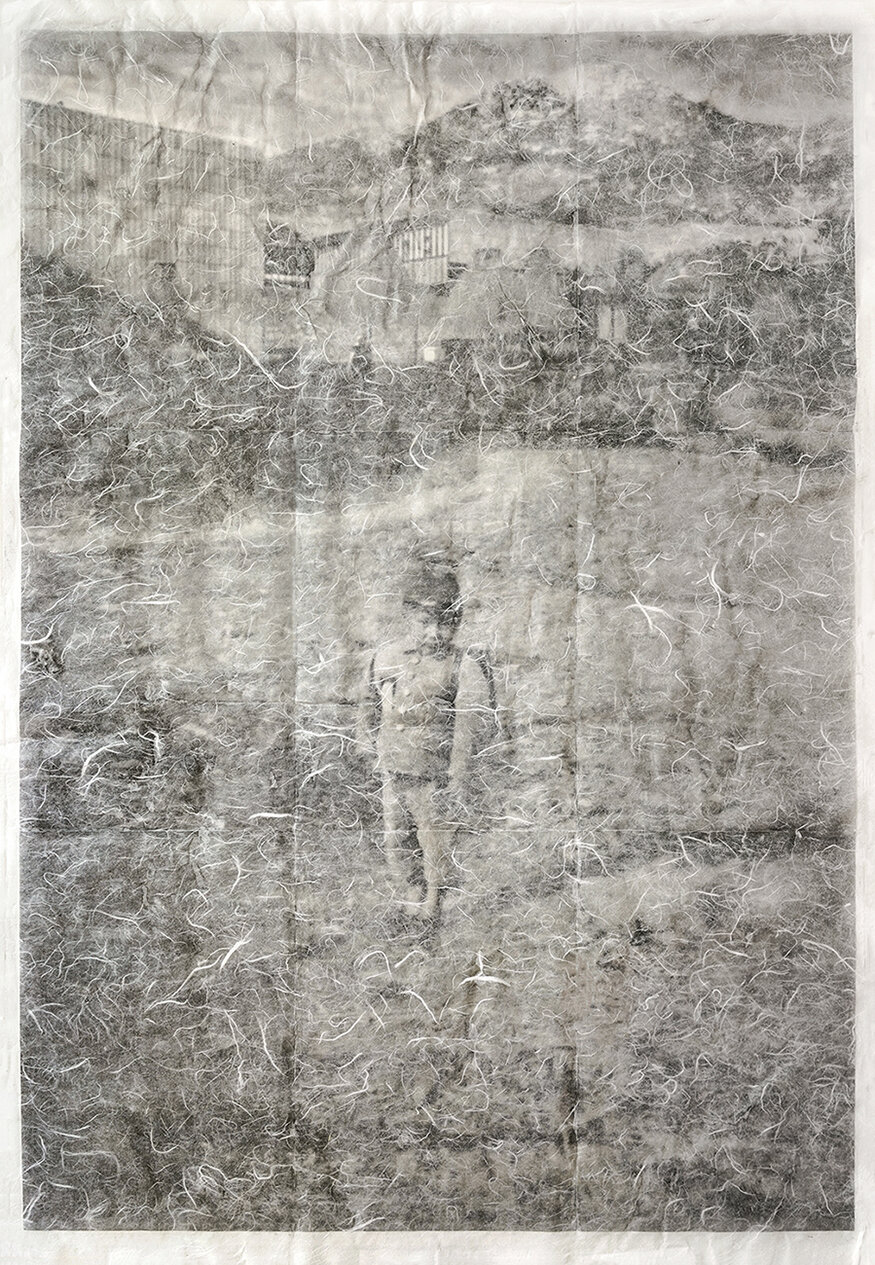

SOOMIN HAM

Soomin Ham, Scent in the Wind, from the Portraits series, 2018

Archival Pigment Print on Hanji Paper, 37 x 25 inches. Edition of 5 + 1AP. $2800.

Soomin Ham, School Boy, from the Portraits series, 2018. Archival Pigment Print on Hanji Paper, 37 x 25 inches. Edition of 5 + 1AP. $2800

I was astonished by the tiny black and white photographs my grandfather had made in the late 1930s and early 1940s. He was not a professional photographer but he had an artist’s sensibility, and this would have been lost to me if not for the box of photos I found after he was gone.

The photos sat before me, faded and worn, but the images were alive with a fragile beauty of expression and gesture. Except for a few photos of my grandmother, the portraits were of people I didn’t recognize. But the candid images were haunting and I started to wonder. In my imagination, I began to create small visual poems, woven fabric of memory and dreams. It was then that I decided to give life again to these lost images.

After exploring and gaining a deeper understanding of these photographs, I began to alter the images to create the “Portraits” series. These new images are reconstructed as composites where the past and present coexist and resonate.

ALICE HARGRAVE

Lake Abiyata, Ethiopia, shrinking and habitat loss, 2021

Photographic Print on Semi-Transparent Fabric, 120 x 60 inches. $1,200, Unframed

The Canary In The Lake

This ongoing project, collaborating with Limnologists or lake scientists from GLEON — Global Lakes Ecological Observatory Network, researches the many diverse ways climate shifts are changing global lakes. This work continues my exploration of climate change-related loss of biodiversity and habitat. The Canary in the Lake alludes to the “canary in the coal mine,” because freshwater lakes function as sentinels of climate change.

At once celebratory of water, and diversity, The Canary in the Lake also questions the efficacy of scientific data as a tool for communicating complex, often invisible phenomena.

I re-visualize scientific lake data from lakes on all continents, creating new patterns that weave together data, archives, photographs, references to lake lore, and the surprisingly vast array of natural lake colors to create "lake portraits.” The patterns create an image of something invisible, whether that be experiential or climate shifts that one cannot see. For example, in Lake Baikal, Russia, warming, zooplankton data are layered into a vintage photograph of the Siberian lake, while Lake Tovel, Italy, clarity and red algae bloom disappearance includes histograms of depth visibility and color sampled from magenta algal blooms. The audio work combines researchers speaking in their native languages, lake lore, lake sounds, Deep Purple’s guitar riff ~ Smoke on the Water composed and written on the shores of Lake Geneva, Switzerland, and a multitude of eclectic lake stories, as told by the most invasive species of them all, ourselves.

JESSICA HAYS

Solar, Molalla, OR, 2020. Archival Pigment Print, 18 x 24 inches, Framed. Edition of 10. $850, Framed.

Wildfires are raging across the western United States, burning up increasingly large swaths of land every year. While fire is a natural part of many ecosystems, the increasing presence of larger, faster, and hotter fires is a reminder of the rapidly changing environment. This work explores solastalgia, which describes emotional and existential distress caused by negative environmental change, generally experienced by people with lived experience closely related to the land. Many of the causes of these changes, such and wildfires, drought, or mine contamination create a sense of powerlessness in conjunction with a lowered quality of life or traumatic events. Lands integral to our identity, our livelihoods, and our wellbeing are shifting and changing without advance notice outside of our control.

The experience of a wildfire is all consuming. It crowds out your vision. The pillar of smoke is unmistakable as anything else. Our communities are facing collective traumas as we wait for news about the spread and containment, constantly refreshing web pages and data bases. Families come home to piles of ash right next to intact homes. Wildfires have no mercy. The day to day struggles of normal life continue on as fires rage outside our windows, setting our lives in a scene of gray oppression. These photographs examine the immediate aftermath of megafires on surrounding communities and what the experience of local fires are like, interweaving narratives of personal struggle, climate change, and collective trauma.

KEVIN HOTH

Death Valley 01, 2018. Archival Pigment Print, 22 x 32 inches, Framed. Edition of 10. $2000, Framed

This series began with a question. How can I show the expansive space all around me in a single two-dimensional image? After some experiments, I realized I could use a mirror in the landscape to join the space behind me with the space in front of me. The series clicked into place when I joined the horizon line behind me to the one in front of me. In this way, I create a temporary landscape that exists only in the captured image. The title refers to the sensation of being able to sense in all directions even if my eyeballs and my camera can only see in one. I began the project using a circular mirror as a reference to the shape of the eyeball and the fact that all images are projected as true circles and then cropped by the camera. I have branched out into using square mirrors as well as cracked and broken mirrors. Natural spaces – those without overt human corruption – are spaces that fill me with peace and act as an antidote to our man made world of information overload. My desire is to show how I experience these spaces, but also to comment on how many people interact with them–mediated through screens. These are abstracted landscapes and cityscapes; they are disjointed much like our current attention span. The mirror can evoke the sensation of feeling all the space around us at one time, but it can also show how we are experiencing these places as visual fragments.

KEI ITO

Burning Away #2, 2021. Unique Silver Gelatin Chemigram (Sunlight, Honey, Various Oil), Metal Frames, 102 x 43 inches (Eight Framed 24 x 20 Prints). Unique. $15000

My work addresses issues of generational connection and deep loss as I explore the materiality of photography. They deal with the tragedy and legacy passed on from my grandfather who survived the bombing of Hiroshima, and the threat of today’s nuclear disaster. Before his passing, my grandfather told me the day the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima “...was like hundreds of suns lighting up the sky.”

Drawing upon my grandfather’s words, I mainly use the techniques of camera-less photography, exposing light sensitive material to sunlight, and often timing the exposures with my breath. On top of the exposing process, the materials and objects used to create an imagery on the prints always have a conceptual significance tied to irradiated personal and collective trauma. My art practice emphasizes the materiality of photography as it channels the origin and the fundamental idea of the medium; I seek to push its boundary by re-introducing the very early-age of photographic techniques into today’s image saturated world.

Burning Away utilizes honey and various oils on a sun-fused silver gelatin paper in a recreation of the numerous stories by survivors seeking to heal the charred trauma. The bomb released a roaring fire ball that matched the temperature of the Sun itself. The heat vaporized the people near ground zero and left devastating burns on those left alive. With a scarcity of even basic medicine, the survivors treated their burns with honey and various oils such as cooking and motor oil. They were unaware of the invisible threat that was implanted within their bodies like a second bomb waiting to go off. It was their children and grandchildren who were witnesses to these cancers and the numerous fights. The pattern of the print depends on the type of oil used on the paper, creating various microscopic like images that may remind one of cancer cells.

JOE JOHNSON

Office Hours with Joe Johnson, 2021. Risograph Printed in White and Black Ink on Light Gray Paper, Tab-Stitched with a Screen Printed Dust Jacket. 12 x 9.75 inches, 124 pages. Edition of 100. $50

Office Hours with Joe Johnson, 2021. Risograph Printed in White and Black Ink on Light Gray Paper, Tab-Stitched with a Screen Printed Dust Jacket. 12 x 9.75 inches, 124 pages. Edition of 100. $50

The artist's book "Office Hours with Joe Johnson" contains 79 photographs made during my academic office hours at the University of Missouri. These images are presented in combination with anonymous truncated communications, both official and unofficial, from student to teacher. In an edition of 100, Office Hours is risograph printed using black and white ink on light gray paper, pad-stitched with a screen printed dust jacket.

PAMELA LANDAU CONNOLLY

Fly in Amber, 2021. Cloth-Bound Clamshell Box with Eight, 8-Panel Fold-Out Chapters, Printed Digitally on Inkjet Paper. Artist's Maquette 2 of 2. $650

Fly in Amber, 2021. Cloth-Bound Clamshell Box with Eight, 8-Panel Fold-Out Chapters, Printed Digitally on Inkjet Paper. Artist's Maquette 2 of 2. $650

‘Fly in Amber’ gathers photographs made of my three daughters over the last eight years. The images tell the story of the last days of childhood and motherhood from the vantage of the empty nest. The collective meaning of the group of images supersedes the import of any one moment.

The eight chapters are housed in a cloth-bound, archival, clamshell box. The 8-panel, accordion-fold structure invites the viewer into its rooms and gardens, the cloistered domestic spaces that hold so much portent. The book’s unique folding structure allows one to create different image relationships that parse together, like the moving light of day, multifold stories, and relationships. On the verso of each unfolded page is a single, large image in counterpoint.

The book opens with a dedication to Lady Hawarden, a relatively unknown 19th-century photographer who created hundreds of evocative portraits of her daughters, pulling back the curtains of their English townhouse to let in the light.

Artists’ Maquette no.2 of 2

An edition of 50 books + 3 A.P.s are currently in production and will be available for sale in Fall ’21.

GIOVANNA LANNA

Rio de Janeiro, BRA, from the Tarja Preta series, 2020. Gelatin Silver Print, 6.75 x 6.75 inches; 13.78 x 13.78 inches, Framed. Edition of 5 + 2AP. $1500, Framed.

Giovanna started the project in 2020, when she looked deeply into the study of Cannabis, as she has a long-standing relationship with the plant for medicinal use. From a personal point, Giovanna wants to draw attention to a public health problem. It is a fact, that there is a slowness in the regulation of the use of cannabidiol, the plant oil that does not contain THC, for medicinal treatments here in Brazil. In the case of multiple sclerosis disease, for example, although the medication is regularized, the purchase prices are still exorbitant because most of the production is imported. In addition, there is still a huge prejudice from society in general, from religious and political groups regarding the medical use of Cannabis.

The sale of cannabidiol was regularized under medical prescription, as a black-stripe medication.

In the Tarja Preta series, Giovanna Lanna uses a large format, 4x5 negative camera. In her images, she opposes a subject that is still marginal in contemporary Brazilian debate to a technique with a language closer to modernist photography.

“The experimental side of photography interests me a lot. Everything appears in my head as a composition from a blank board where the elements are arranged, opposed, balanced, out of place, which turns out to be the opposite of the process of documentary photography. There is no decisive moment, everything is extremely planned before pressing the fire button. I love the way analog photography works, in addition to its visuality, there is a need for control and precision within this handicraft process that is extremely poetic. In a world where we have billions of images shared daily, I am proud to spend hours and sometimes days preparing to take a single photo."

CHRISTIAN K LEE

Black Gun Owners: Fraziers, 2021. Archival Inkjet Print from Scanned 4x5 Negative, 24 x 16 inches, Framed. $1500, Framed.

Black Gun Owners: Devin, 2021. Archival Inkjet Print from Scanned 4x5 Negative, 24 x 16 inches, Framed. $1500, Framed

Growing up in Chicago I only saw guns in the hands of people that looked like me when we were being portrayed negatively or it was always that item that was used by officers to justify killing black people. This phenomena made it difficult for me to grasp the idea of wanting to own a gun. In short I was terrified to be around them because I only saw it around dead black people or black people that society deemed as bad or dangerous, of course this is simply not true. This project is one part a therapeutic exercise to recondition myself on what society has told me about guns. It is also an attempt to recondition others!

JIATONG LU

The Secret Place With Nowhere To Hide #1, 2020. Archival Pigment Print, 25 x 20 inches, Framed. Edition of 10. $1000, Framed.

The Secret Place With Nowhere To Hide

As a child, when I was beaten and scolded severely by my family at home, a place I could not escape from, I would instinctively dissociate myself from that combat situation. I would imagine myself in another shadowy space far away, where I could float or sink without gravity. My body would become numb instantaneously and I could not feel any pain. Whenever I was overwhelmed with emotions of helplessness or alienation, I would fantasize about escaping to an unknown place, a forest or an island, where no one knows me, and I do not exist for any purpose. That process would bring me calm and peace temporarily.

Growing up, the language people used around me had always been negative and violent. However, my experiences with photography felt completely different. Just like how it was in my childhood, photography would take me to other worlds, which could not be reached in reality. Since children are too young to fight back, or change their terrible situation directly, I am curious about how they would create an imaginary “safe haven” for their own “self-redemption”, and to internalize the trauma that they had been through. In this work The Secret Place With Nowhere To Hide, follows the fragmented feelings of my childhood, I am trying to internalize my inescapable traumatic memories, the broken relationships, and the feelings of being alienated. This project explores the relationships between self and other, intimacy and isolation, as well as the body memories and internal emotions, and attempts to show how photography can conceptually reconstruct the inter-relationships among them.

HOLLY LYNTON

Les, Honeybees, New Mexico, 2007, from the series Bare Handed, 2007. Archival Pigment Print, 30 x 40 inches, Framed

Edition of 5. $3500

The photography series Bare Handed presents a portrait of Americans facing their relationship to nature as technology alters their environment. Instead of portraying the effects of big agriculture on their livelihood and natural resources, these photographs depict people who honor the land through their dedicated stewardship. This decade-long series celebrates an almost spiritual practice that goes far beyond the yields of a harvest, and highlights traditions edging toward disappearance. Initially, I searched for specific individuals who worked in nature using an approach that allowed for and encouraged a unique vulnerability. I wanted to make photographs of people who gathered sustenance by working in tandem with the environment rather than with the idea that they would conquer it. These singular portrayals quickly and naturally revealed more complicated and intertwined histories, prompting me to expand the series and photograph various regions across the US. My images of these communities extend beyond simple portrayals of organic farming and the false narrative of victimhood to reveal what sustainability means to those living and working in rural America. A year after starting this body of work, I moved from New York City to New England farm country. This relocation reaffirmed my interest in the ethos of sustainability and local farming, and reinforced my desire to continue telling stories of the land. My passion and drive were further ignited by the sheer risk of exposure on display in those first photographs. The beekeeper approaching the hive with no protection, the unguarded trainers at the wolf sanctuary, and the catfish noodlers wrestling their 70-pound catch all showed a commitment to these unmediated methods of working that was intoxicating to witness. Over time, the implied danger in their circumstances receded and the meditative aspects of their practiced movements came to the fore. Effortlessly synchronized choreography had developed from years of being enmeshed in their environments. Trust in these ritualistic motions allowed for efficiency, safety, and consistency-—all necessary elements in these sustainable practices. My goal is to convey in a single frozen moment the feeling—heat, light, and even smell—of witnessing a continuous action and evoke at least some of the majesty that motivates the people I photograph. Their repetitive, dancelike movements captivate me. An ongoing fascination with motion and gesture stems from my childhood experience as a ballet dancer. There is an inherent tension between the swiftness of creating a photograph, which happens in a fraction of a second, and the part of my practice that involves watching and waiting for the right moment to make the image. Sometimes, it is hard to know when that right moment is, but I aim to photograph the quintessential gesture to create an image where movement, environment, and light conspire to create in a kind of magic. Many of the people who work the land or go to sea are waiting and watching as well, giving themselves over to that which they cannot control and waiting to see what magic nature will give them in return.

SARAH MALAKOFF

Concentration on the Bear Rug, 2020. C-Print, 26 x 22 inches, Framed. Edition of 7. $1200, Framed.

These images are a collection of private spaces that ask the viewer to imagine the people who inhabit them. Possessions, whether purposely displayed or left behind haphazardly, hint at family history, relationships, preoccupations and desires. The quiet moments of the images, devoid of human presence, perhaps belie the tangle of family interactions that have transpired or are unfolding outside of the frame.

NOELLE MASON

Valley of Shadows (Sasabe), 2021. Wet Plate Collodion, 4 x 5 inches. Edition of 3 + 2 AP. $1000, Unframed.

Valley of Shadows is a body of work about the phenomenological effects of vision technologies on the perception of migrants and refugees crossing the border into the United States. A 4x5 camera is used to make wet-plate collodions from appropriated infrared images. The images used in this series were collected from the United States Border Patrol and border-watching vigilantes. This translation from digital image to 19th century process is intended to expose the imperialist worldview historically embedded in digital imaging. The use of wet-plate collodion transforms infrared surveillance images into unique objects that resemble the landscape photography made during the period of westward expansion in the United States. In so doing the migrants and refugees of today become a visual reverberation of the American migrations of another era.

ELIZABETH MCGRADY

Martian Mother, 2020. Handmade Artist's book (Accordion Inkjet Print),

11 inches x 531 inches (44.25 ft), Unfolded, 58 pages. $375

Martian Mother is both an ongoing photographic art installation and book that will be sent to pioneers of space exploration that proposes a mission, sending myself to the planet Mars with in vitro fertilization equipment. Traveling with that equipment, I would be impregnated thus giving birth to the first Martian baby and becoming the first Martian mother. Should another like-minded individual volunteer for this one-way trip to another planet, they will be incorporated into the center of this existing framework.

My work is firmly rooted in speculative fiction as I incorporate scientific theory, mythology, and the female experience. I am examining queerness and the intersection between the body and the universe through the lens of fertilization and space exploration. The work is ongoing, with this installment focusing on everything up until the moment of birth, theorizing that the moment of birth and the moment of the singularity are inherently tied. I examine myself as Host to discuss the female body in regards to reproduction and land, examining the physical landscape of both Mars and the universe as analogous to the female reproductive system. The work theorizes that the female experience is cyclical, drawing on mythology and core tenants of Celtic Paganism, to explore the inter-dimensional slippage of time as it relates to the physicality of black holes.

Further, this work relies on a different definition of female than the biological. The pagan community has expanded the understanding of the female body to include trans and gender nonconforming individuals. Femaleness does not rely on biology, rather on the female experience, a state of being. When the uterus is discussed, it is not as the organ itself, but the properties inherent to the cyclical female experience. This is a crucial aspect of the discussion of future civilizations and the queering of our understanding of science.

CAROLINE MINCHEW

Walking in the Greenhouse, 2021. Archival Pigment Print, 20 x 24 inches, Matted and Framed. Edition of 4 + 2AP. $2000, Framed.

The last of something is when we begin to pay attention. Last day of school, last kiss, last bite, last grandparent. Growing up I spent time at my grandmother’s expansive herbal garden in Jacksonville, Florida. It was hot, humid, and she put us to work. Repotting, digging — her one-liners and criticisms are now imbedded as I learn to garden myself. In December I got news that her health was failing, rapidly. Her inherent knowledge of plants, knowing a singular place, and cultivation – will one day be gone, and what will become of the plants themselves? Tropes of femininity and gardening recall “healing” and “reciprocity” - and while her actions do, her agency and creativity are just as strong. Her story tells a larger one of using the land to make more for oneself, why putting our hands in dirt feels good, and how we can read time through growth and decay.

I photograph the natural world as a means to create visual, organic metaphors for time, natural cycles, and darkness as a sign of rebirth; both in the context of myself and the larger non-human world. As a photographer, I continually return to the landscape as the basis for my work – as a physical tool for intimate, self-contemplation and discovery on the intersection of art, story, and science. I’m interested in how photography and organic objects can represent both the metaphysical, and the direct human relationship to nature.

ROBYN MOORE

Being in the Land (Shenandoah), Stony Man Peak, Skyline Drive, 2021. Photopolymer Gravure, 20 x 23.5 inches, Framed. Edition of 8. $1200, Framed.

Being in the Land is a series of photographic works inspired by my desire to make contact with the memory embodied by landscapes. By making aspects of the land’s more latent phenomena visible and material I hope to understand more about its biological capabilities and significance. I rely on my art practice to facilitate empathy and the imagining of others' worlds, lives, histories and experiences and, in so doing, hope for a kind of access to what otherwise would remain lost or irretrievable.

The works submitted to UNBOUND10! are photopolymer gravure prints. I work with this process because it is unpredictable, giving and revelatory. Indeed, I feel the experimental nature of this process allows me to access what cannot be seen with a more conventional sense of sight. The inky sensuousness of photopolymer gravure allows me to explore the deeply-embedded but subtle emotional and psychological undertones of what persists in the land: human histories, animal histories, deep time and the limits of our own knowledge. I hope the images from Being in the Land materialize and amplify this sense of felt presence, which seems both to emanate from the land as much as reverberate throughout it. I also hope these images testify to the intelligence inherent in all landscapes.

COLLEEN MULLINS

Expositions are the timekeepers of progress, 2020. Archival Pigment Prints on Hahnemühle 100gsm Rice Paper, 3M Post-It, and Tops Legal Notepad paper, Double-Fan Bound, Cased in Duo Bookcloth, and Hand Cut Bristol Board Wrap. 8.6 x 6.3 x .63 inches, 64 pages, Edition of 7 + 2 AP. $1400

This work is a poem about removal and mass misinformation. It is an examination of the issue of monument removal in the United States, though the story of one town, and the effigy of a president who never belonged there in the first place.

At 4am on February 28, 2019, after a long, contentious battle, an election, and a rainy winter, a statue of President William McKinley was disassembled and taken from the town plaza of Arcata, California. It was the first Presidential statue removed from public view in US history.

On one side of the removal debate, were a vociferous group of activists who called the 25th President a racist, and slave owner who did not deserve to be in their town. On the other, those with fervent nostalgia, who also resented a town council that did not seek a vote of the people. But the point of interest that drew me to follow this story for over a year and all the way to Ohio (where the statue is now in storage) was that in truth, neither side seemed to have any idea what exactly McKinley did wrong, or that he had fought for the Union in the Civil War. Many thought the effigy in the square was a logger, as there is a town called “McKinleyville” five miles north.

Over the 100+ years it was in place, the statue was climbed by jubilant students from the local university, defaced with caustic substances, had cheese stuffed in its nose, had its thumb sawn off (later recovered and re-attached), and decorated for holidays as everything from a choir boy in white-face to an angel. None of these acts have had anything to do with the president himself. The statue was a talisman; a mountain; a meeting place. It functioned not as a symbol of white oppression of the native Wiyot, nor the imperialist tendencies of the president himself, but simply as a mascot. Yet, the robust conversations in the community, taken slowly and methodically, helped all sides to see each other, and led to a previously improbable act of neighboring Eureka, returning Wiyot land, stolen in 1860 after a brutal massacre.

Public Collections:

Humboldt State University, Arcata

University of Colorado, Boulder

SCOTT MURPHY

S.L.1 and the Mystery of the "Baby-Killer" Schütte-Lanz Airships, 2021

Unbound book, Found Text/Imagery, Digital Collage, Pigment Prints

3.5 x 5 x 1inches, 66 Pages (unbound in a wrapper). Edition of 6. $330

Life is just one damn thing after another.

-Elbert Hubbard

There is much beauty in the world. So much of it surrounds and is infused within us, it can often be hard to fathom. Yet, we are immersed and surrounded by endless suffering. And death. Not just the horrors of distant conflagrations, but those seemingly around every corner. This is not all about looking outward either, for indeed, we cannot escape the awareness of our own inevitable end. Life is incurable after all.

In the making of art, I find respite from the darkness that often feels as though it is endangering the light. A quiet, meditative process of manipulating materials with my hands is at the heart of all the creations I devise. In the making of paper by hand, or photographs with raw chemicals, or the binding of books, I find joy and stillness.

However, this desire to work slowly and with a myriad of varied tactile materials does not negate the usage of digital methods. Instead, my answer is to find a way to integrate analog, historic, and anachronistic methods with twenty-first century virtual technologies. To do so in a manner that enhances the subject matter and produces art which is stronger from this marriage of the antiquated and modern.

In the artworks before you, I cannot pretend to erase the depth of despair that living can foment. I do hope to offer a salve. A salve that unites old and new, beauty and death, spirit and body.

RACHEL PHILLIPS

Intrepid Girl Photographer Books, 2019. Artist Made Covers Wrapped Around Vintage Agatha Christie Paperbacks, Approximately 7 x 4.5 x .5 Each. Edition Varée of 5 + 2AP. $400

“Very few of us are what we seem.”

~Agatha Christie

Intrepid Girl Photographer is the fictional heroine of an imaginary series of eponymous paperbacks penned by an invented author named Tabatha Misty. The series riffs on pulp and detective fiction, as well as the vocabulary and tropes of photography, to create an alternative feminist footnote to the history of a medium in which women photographers are too often only notable exceptions to the rule—appearing most often within photography as subject or muse, but not picture-maker. Tabatha Misty is inspired by legendary mystery author Agatha Christie who, in addition to being the world’s best-selling author after William Shakespeare, was also an avid amateur photographer.

PROCESS

Each book in the series is an original, vintage paperback by Christie to which a newly made, yet carefully distressed, cover has been adhered, resulting in a unique altered book work. Each cover is crafted from an extensively researched collection of design elements combined with original photographs, invented titles and blurbs, and vintage illustrations from the artist’s collection.

MIORA RAJAONARY

Hanta, 2018. Archival C-Print, 33 x 33 inches. Edition of 8 + 1AP. $2100, Framed.

« A lamba is the traditional garment worn by men and women that live in Madagascar. The textile, highly emblematic of Malagasy culture, consists of a rectangular length of cloth wrapped around the body. »

LAMBA is a photography project intended to show how this Malagasy garment, serves as a valued symbol of the island's cultural heritage, beyond its role as elegant and ornamental clothing, We, Malagasy, offer cloth in return for blessings, or to demonstrate ethnic identity, status and ties of mutual respect, love and loyalty. For instance, men offer cloth to their brides at marriage; bride and groom are encircled in a single cloth to symbolize their union; and descendants honour their ancestors by wrapping their remains in a lambamena, the silk burial shroud, during traditional rites.

This project takes form as a portrait series inspired by the traditional of African studio portraiture, and shot with a medium-format film camera. For each picture, I systematically used a lambahoany (a printed cotton lamba typically featuring a proverb on the lower border of the design, presently the most commonly worn type of lamba) as a background.

MEGAN RATLIFF

Inside the Boudoir (001), 2021. Archival Pigment Print on 68lb UltraPro Satin Paper, 60 x 44 inches. $3500, Unframed.

Fundamentally my work questions the assumed analogue-digital divide in conceptions around photographic history and practices. I upend common assumptions pertaining to this divide, which ultimately relates to photography's inherently interdisciplinary visual economies My artistic practice in analogue photographic processes is punctuated by traditional academic research in the history of photography and visual anthropology. This is both informed by the inherent materiality of analogue photographic processes and their scholarly conceptions of photography as an image-making technology.

Inside the Boudoir examines my personal collection of 80’s and 90’s boudoir photographs, medium format negatives procured from EBay, depicting women in various states of undress. This work complicates photographic genres, which are sometimes discussed interchangeably (glamour and boudoir photography) and asserts that these genres operate as part of cultural practice in negotiation with photographic technology and associated ephemera (e.g. ‘How To’ technical manuals). It also negotiates perspectives regarding private and public domains, agency, and obfuscation as garnered from photographs that are only a couple of degrees away from being tossed in the trash.

RENEE ROMERO

Garrett and Ariana, 2020. Archival Pigment Print, 14 x 11 inches; 20 x 16 inches, Matted and Framed. Edition of 10. $550, Framed

The makeup of my own family has pushed me to document them as much as possible to piece together my own identity and place in their world. Family photographs are meant to hold the weight of familial relationships, milestones such as births, deaths, and everyday moments. My father died prior to my birth, and the only family that I know is my maternal one.

I often reflect on how the experience my mother had raising me is vastly different than my own experience in motherhood. I’m privileged to have an experience of motherhood that has security, support, and time to soak in the in between moments of play, rest, exhaustion, and the domestic labor and constant care that comes with being a stay at home mother.

While I experience the happiness that comes from motherhood,I also find myself in many moments of frustration, being overwhelmed with the never-ending tasks of motherhood within our home.

Documenting our journey together through self portraits gives me the space to create while constantly mothering, remembering the fractions of time that I can find joy in our lives within our homes, and hold onto the moments that slip away too fast.

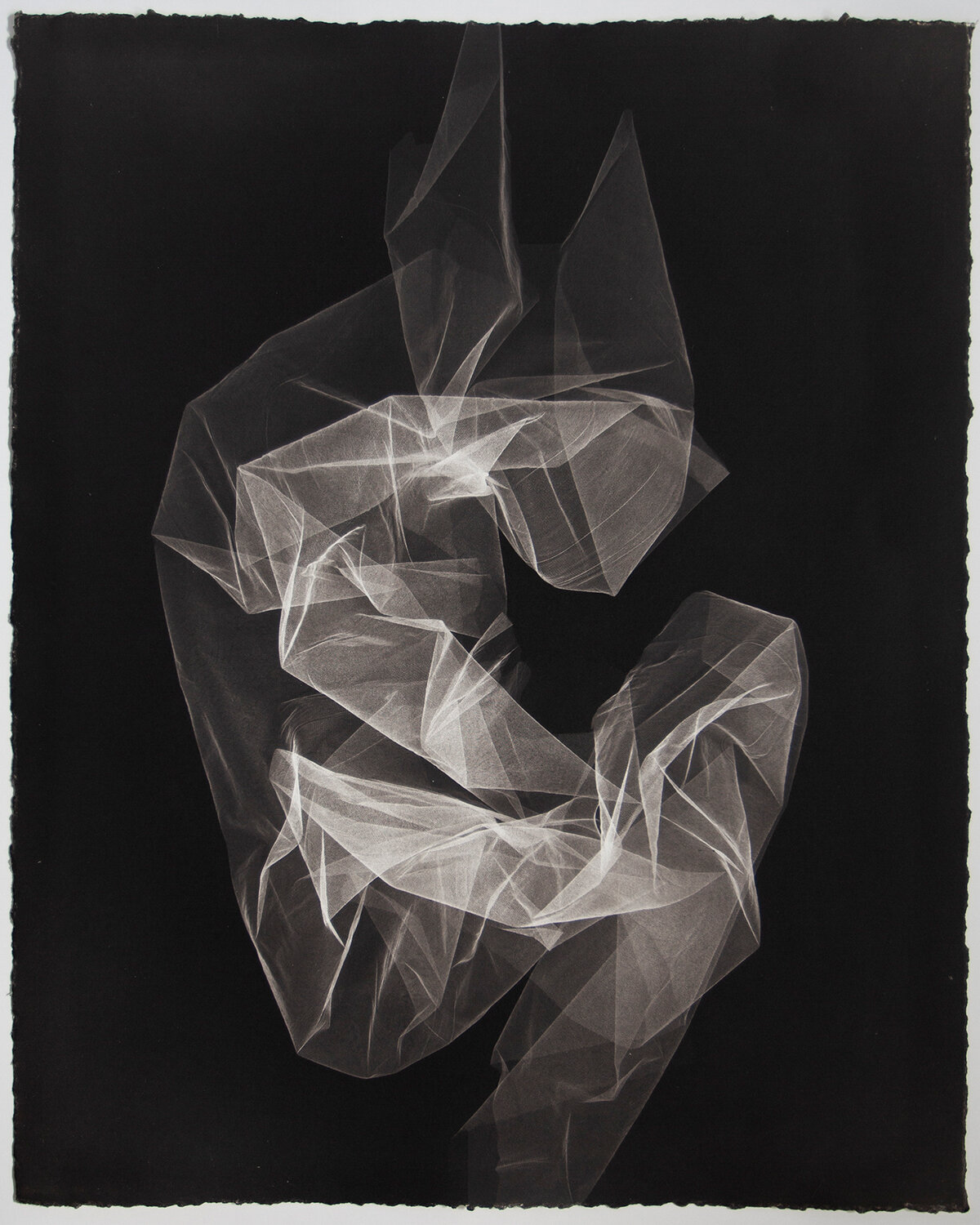

KATHERINE DEMETRIOU SIDELSKY

Screening, New York, 2020. Platinum/Palladium Print, 23.75 x 19.75 inches, Framed. Unique. $1800, Framed.

Restricted to my home-studio, in a house shared with my family during 2020’s earliest Coronavirus containment zone, I created three-dimensional impressions of our emotional space using a veil and a 3’x5’ black base. “Boundaries of the Lucid Veil” considers the shifting space between myself and others, in a time of newly imposed restrictions. By insulating ourselves in protective environments, we isolate ourselves from the world and reality. The silk veil forms a topography of imaginary walls that I shape only to be captured with the camera. As we scan our mind and body for clues, asking ourselves and each other “how do you feel today?” the unseen is as informative as the illuminated in the oscillation between what we imagine and what we know to be true.

PAUL STEPHENSON

Fireworks on Man Ray, 2020 and 1920. Forced Collaboration on Original Work by Man Ray, 11.2 x 9.1 inches; 18.06 x 14.94 inches, Framed. Unique. $6500, Framed.

My current practice is centered on working directly onto existing ‘original’ works of art by other artists. This is in part inspired by the definition of graffiti that Barthes’ proposed, “what constitutes graffiti is in fact neither the inscription nor its message but the wall, the background, the surface (the desktop); it is because the background exists fully as an object that has already lived, that such writing always comes as an enigmatic surplus... that is what disturbs the order of things; or again: it is insofar as the background is not clean that it is unsuitable to thought (contrary to the philosopher's blank sheet of paper)”. In working directly on an existing artwork I wanted to achieve what Bathes describes here as an enigmatic surplus, my instinct was (and still is) to ‘disturb the order of things’ by working on ‘backgrounds’ that exist fully as objects and that have ‘already lived’.

As my practice has developed I have moved to superimposing images on existing works. This still has some links to graffiti, but now owes more to one of the other ‘pillars of hip hop’; deejaying. By superimposing images I began ‘remixing’ artwork by other artists, deejaying with paintings. This working method has parallels to the critical thinking of Nicholas Bourriaud and specifically his essay Postproduction. His concept of an artwork having a ‘script like’ value, and that 'using' an artwork moves beyond appropriation, and its implied ownership, to a new culture of the use of forms based on a collective ideal of sharing, or what I would call collaboration.

This work is a collaboration between myself and Man Ray. The source work is an original, lifetime print signed by Man Ray (and Curtis Moffat), the subject is the composer Thomas Beecham. It was printed by Man Ray and Moffat C1924 in Paris. The overlaid image, the 'fireworks' are bokeh from coloured lights; a photographic abstraction of pure light and colour.

DANA STIRLING

Pride of Madeira, 2019. Archival Pigment Print, 20 x 16 inches, Framed. $1500, Framed.

As a teen and young adult, I spent all my time inside my room. I always felt alone within these walls, alone when I was out, alone when I was with friends, just alone. Family was not a comfort, it was a cause for much of the stress, anxiety and mainly the sadness I felt. My mother, even though we didn’t speak about it often, suffers from clinical depression. When you are young you just think of it as if your mom is just a little sad, so it makes sense that you also are – a little sad sometimes. As I grew older, and my frustration of the situation grew, I found myself hiding in my room for days, hours and years, buried with my head down in this sand prison. I just felt sad all the time. In this loneliness, I found comfort in photography. Photography allowed me to take my inner dialogue and bring it out by using still life as my personal coded language. I was able to communicate with these objects better than people. They told the story I was not able to. Now, years after moving as far as I could from that room, I find myself still being sad. Photography has become not just an escape but now also my burden. When I don’t photograph I am sad, and when I do photograph my images are sad as well as if I am no longer able to escape the cloud of sad that is above my head. Why am I Sad? is my exploration of my personal relationship to photography and the world that I see through my camera’s lens. It is an open question that I don’t intend to answer but I hope that I can find comfort in it once more. This work in still in progress.

ELIZABETH STONE

You Are Here #72, 2021. Chemigram - Silver Gelatin Paper, 20 x 16 x 4 inches, Unframed. $900

You Are Here #310, 2021. Chemigram - Silver Gelatin Paper, 20 x 16 x 4 inches, Unframed. $900

Visual artist Elizabeth Stone is propelled by the exploration of perception, perspective and the evolution of making. Transformation is at the heart of her work as she investigates the materiality of the photographic medium.

Over the last decade Stone has been questioning the dual aspects of photography, the idea of the negative and the positive, each demanding attention. In thinking about the whole, a constant interchange of destruction and creation drives her impulses in making.

Currently her work utilizes analog materials to investigate the photograph as a three dimensional object. She seeks slow, time consuming practices that meld the hand and mind. In the YOU ARE HERE project, oil and water, immiscible elements, are bound to gelatin silver photographic paper to create topographic abstractions. This cameraless process called a chemigram, records the interplay of light and chemistry on paper. After physically sculpting the paper to shape peaks and valleys, Stone surrenders control and allows the materials to take over and form their own living patterns. Informed by decades of roaming and closely observing the Western landscape, Stone studies the impact of human presence and our narrow perception of time. Inspiration comes from artist John Cage’s chance controlled musical compositions, Imaginary Landscape No. 1 - No 5.

Process drives Stone’s work as she continues to push and pull at the edge of what defines and how we see the photograph.

JERRY TAKIGAWA

Balancing Cultures, 2021 (page). Offset. Stochastic Screens. First edition. Softbound with Dust Jacket, 9 x 7 inches. $50

Balancing Cultures, 2021 (page). Offset. Stochastic Screens. First edition. Softbound with Dust Jacket, 9 x 7 inches. $50

In “Balancing Cultures,” I am working with layers of meaning, memory, family, and— centrally—the actions and consequences of Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066. Issued in 1942, it caused the incarceration of 120,000 American citizens and legal residents of Japanese ancestry. My recent discovery of family photographs, taken in the WWII American concentration camps, compelled me to examine my family’s unspoken feelings of shame and loss. I wanted to give voice to those feelings, which they had kept concealed for fear of retribution.

“Balancing Cultures” began as a personal identity project and grew into an examination of the United States’ political and social injustices against its Japanese population. Through my family’s WWII experience, Balancing Cultures” brings empathy to history. Piecing together this historical puzzle of my history, I felt this was something we all do. We are the puzzle—our family, friends, community, and society—all puzzles within the big puzzle of the universe. The images are temporary collages using archival family images, slightly out of focus to befit the workings of memory. The superimposed layers are a stage where suppressed feelings can be witnessed. Making these feelings public is a betrayal—revealing family secrets—yet, it’s healing.

EO 9066 was a dark chapter in American history that injured its victims and succeeding generations in ways both seen and unseen. Emotional trauma has no statute of limitations and silence is a powerful transmitter of emotional trauma—a complex legacy for the next generation. “Balancing Cultures” reminds us that racism, hysteria, and economic exploitation are attributes of xenophobia. Add to that the renewal of violence against Asians today. If silence sanctions, then documentation is resistance.

The “Balancing Cultures” book is 96 pages, 7 x 9, Smyth sewn, softbound with dust jacket, printed with stochastic screens (20 microns).

VAUNE TRACHTMAN

Bound, 2021. Photopolymer Gravure with Surface Roll on Shiramine Washi Paper, 11 x 14.75 on 14.25 x 17.5 Paper, 15.63 x 18.88 inches, Framed

Edition of 8 + 3AP. $900

NOW IS ALWAYS was begun during the Great Depression when my father, Joseph Harold Trachtman (1914-1971), shot a few rolls of film near his father's drugstore in Center City, Philadelphia. Nearly 90 years later, my sister found the negatives and gave them to me. Working from my father’s original negatives, I've combined the people from his neighborhood with my own images, many of which were shot from windows and moving vehicles. NOW IS ALWAYS is our collaboration across time.

My father lived in Philly his entire life, and his images of friends and neighbors are firmly rooted in one place and time: the corner of 19th and Girard during the Depression. My images, on the other hand, are much less rooted. This is probably because I was pretty much on my own after my parents died– my father when I was five and my mother when I was 15. My most vivid memory of my father is his leg, because that’s about all I was tall enough to see of him. His most vivid memory of me? I will never know. And yet in this work we manage to speak.

After my parents died, I was rarely in one place for very long. Often the view out a car or train window felt more like home than wherever I was living. Over time, I've developed a kinship with blurred bridges and highways, trestles and roofs, the husks of industrial towns racing by at two or three in the morning. In this work, my father's life becomes part of these landscapes– our shared and evanescent homes.

There is obviously a personal aspect to NOW IS ALWAYS, but I want the work to be more expansive than a dialogue between the father I didn’t know and the daughter he knew only as a child. In NOW IS ALWAYS, I want to create a feeling of collapsed-yet-expanded time. Yes, I want to see what my father saw, and yes, I want him to see what I see. But I also want the viewer to look at the past, and I want the past to look right back; I want the viewer and the subject to each feel the gaze of the other. And by combining images taken almost a century apart, I also want to seamlessly integrate layers of technology and image-making history: his 1930’s point-and-shoot, my iPhone, his silver-gelatin negatives, my Photoshop files, our shared sunlight and water, the traditions of ink, elbow grease, and an intaglio press.

NOW IS ALWAYS is supported by a grant from the Vermont Arts Council and the National Endowment for the Arts, with additional support from the Tusen Takk Foundation.

PAUL THULIN-JIMENEZ